Cognitive Dissonance

and Evidence Based

Medicine - David

Naylor’s Kergin Lecture

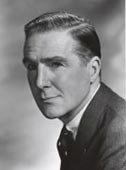

Frederick Gordon Kergin

|

Frederick Gordon Kergin

was born at Port Simpson

in British Columbia in

1907. He began his studies

at the University of

Toronto at age sixteen

and graduated from the

Biology and Medical

Sciences program in

1927. In 1931, Kergin

became a Rhodes Scholar

and spent the next two

years at Oxford University in a Master’s Degree program

in physiology and anatomy, graduating with

first-class honours. In 1934, he began the four-year

Gallie Course in surgery at TGH and obtained

the fellowship of the Royal College of Surgeons

of England in 1935 and that of the Royal College

of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada in 1939.

In 1937, he joined the surgical staff of Toronto

General Hospital and later took the role as Chair

of the Department of Surgery of the University

of Toronto and Surgeon-in-Chief of the Toronto

General Hospital from 1957 to 1966. He was a

pioneer of thoracic surgery in Canada and served as

President of the American Association for Thoracic

Surgery. In1966, he was appointed Associate Dean

in the Faculty of Medicine and was responsible for

developing a new undergraduate curriculum and

planning the conversion of Sunnybrook Hospital

to a teaching institution with full-time faculty. Dr.

Kergin chaired the editorial board of the Canadian

Journal of Surgery for many years and served as a

trustee of the R.S. McLaughlin Foundation.

His major contribution to the University was in

education, particularly in structuring the residency

programs such that an integrated program amongst

all fully affiliated hospitals was established. Professor

Kergin died in 1974, a man with eclectic interests

that included teaching, research and university

administration, as well as many outside of medicine.

(http://surgery.utoronto.ca/events/kergin-lecturers.htm)

|

James Rutka and David Naylor

The 2017 Kergin Lecture was delivered by David Naylor,

former Dean of the Faculty of Medicine and President

Emeritus of the University of Toronto. Naylor’s theme

was ‘Cognitive Dissonance and Evidence-Based Medicine’

[EBM]. Based on his studies of an American religious cult,

psychologist Leon Feininger coined the term ‘cognitive

dissonance’ in 1956 to designate the distress people feel

when reality conflicts with deeply-held beliefs. Cognitive

dissonance is resolved by denying, ignoring, or reinterpreting

the contradictory finding which does not fit with

our biases or beliefs. Naylor drew on his long experience as

a researcher and policy advisor to examine applied health

research, healthcare policy-making, and clinical reasoning,

all viewed through the lens of cognitive dissonance.

Starting with research, Naylor observed that clinical

epidemiology emerged in the 1970s and 1980s as a discipline

that aimed to enhance the rigor of clinical studies

and bring research results to bear more fully on clinical

decisions. These insights were synthesized and presented

to the profession in the early 1990s as ‘Evidence-Based

Medicine’ [EBM]. EBM was described as a new clinical

‘paradigm’, i.e. a system of assumptions, concepts, values

and practices that constitutes a way of viewing reality. It

characterized clinical experience as an unreliable source of

evidence – an apparent devaluation of clinical judgement

that understandably unsettled many surgeons given the

highly case-based nature of their work. Naylor observed

that, more generally, EBM as a paradigm has continued to

struggle with the dilemma of the applicability of evidence

and the unreality of the ‘average patient’. Small effects that

turn out to be statistically significant in giant randomized

trials mean that many patients are exposed to side-effects for

everyone who benefits from a given ‘evidence-based’ treatment.

EBM acolytes often argued that the solution was to

stratify subgroups of patients by baseline risk, assume the

same relative benefit would accrue to all, and therefore infer

that the highest-risk patients would gain the most in absolute

terms. However, studies using sophisticated biomarkers

are starting to overturn this mode of reasoning.

To illustrate this point, Naylor showed us a randomized

trial of the cardiovascular drug Dalcetrapib (Tardif JC et

al, Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2015;8(2):372-82) that initially

found no difference when the drug was compared to placebo.

Use of biomarkers later revealed that the drug was

highly beneficial in one genetic subgroup and harmful in

another. The two effects cancelled, leading to an erroneous

‘evidence-based’ conclusion. Naylor suggested that this

result was a bellwether for the challenge facing the current

incarnation of EBM as ‘the medicine of averages’. He

observed that a counter-paradigm was emerging as biomolecular

characterization of patients continued to advance,

thereby enabling better tailoring of treatments. He predicted

that new molecular markers and other measures such

as functional imaging were likely to compel reconsideration

not just of who received specific treatments, but how we

define disease entities, particularly in disciplines such as

psychiatry, with its descriptive Diagnostic and Statistical

Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM).

Naylor emphasized that consideration of variations in

patient characteristics and anticipated responses to treatment

has been an integral part of expert judgement dating

back centuries in clinical medicine. What is different

now is the convergence of our deepening understanding

of human biology with other factors such as the use

of digital devices to enable continuous monitoring of

patients with sophisticated sensors, improved imaging,

automated treatments based on digital monitoring and

the application of artificial intelligence. Sophisticated

tissue engineering techniques may transform not just

the field of transplantation but surgery in general. This

layering of diverse disruptive forces has meant that the

once-popular term, ‘molecular medicine’, is already

being largely supplanted by terms such as ‘personalized’

or ‘precision medicine’.

|

Just as the emergence of EBM seemed to engender

cognitive dissonance among those attached to other

modes of thought and action, so also was it now ironically

the case that EBM fundamentalists were among

the most vocal critics of personalized or precision medicine.

Naylor cautioned, however, that personalized or

precision medicine was far from a panacea. It had the

potential to provide remarkable improvements over the

“shot-gun approach” of EBM, but many exaggerated

claims were already being made for this latest paradigm

and the potential costs and risks are enormous.

Other countries such as the UK and Australia were

more enthusiastic about precision medicine, and more

thoughtful about developing a reliable knowledge base

and strong framework for funding and using these

concepts in practice. Developing a Canadian national

strategy for personalized medicine was accordingly

among the recommendations made in 2015 by a distinguished

Advisory Panel on Healthcare Innovation that

Naylor chaired for the federal government (link to PDF). Although the Conservative Government

of the day shelved the report, it has found new life under

the current Liberal Government, underscoring Naylor’s

comment that political ideology of all types carries its

own forms of cognitive dissonance. Naylor among others

who promoted EBM in the 1990s had emphasized

that clinical decisions would continue to rest not only

on evidence, but on a given patient’s values or preferences

and the context of the clinical encounter (Naylor

CD. Lancet 1995; 345 (8953):840–2). He wondered if

that list should now be expanded to include cognitive

psychological factors, and particularly in the realm of

healthcare reform, overtly political or ideological considerations.

In support of that point, Naylor reviewed some work

from his early years at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative

Sciences (ICES), showing remarkable variation in rates

of caesarian sections, hysterectomy, knee replacement,

and breast conserving operations. This work had caused

a media sensation when it first appeared in 1994.

Politicians were quick to criticize the profession; physicians

and surgeons in turn rushed to explain away the

variations in very creative ways.

Naylor emphasized that while some practice variations

reflected indefensible departures from rigorously assessed

practice standards, in other instances they reflected

evidentiary uncertainties, different financial and organizational

contexts, and regional or national clinical

cultures. On the latter point, he reminded the audience

that expert panels from different countries would arrive

at different views about the appropriateness of surgery

when given the same evidence and patient case scenarios.

Naylor then showed real-world examples of this phenomenon

in the realm of differences between Canadian

and American practice patterns in use of cardiovascular

procedures after myocardial infarction (Mark DB et al.

N Engl J Med 1994; 331:130-135).

Naylor also summarized several studies led by Toronto

researchers illustrating how errors in cognitive processing

affect decision-making. For example, physicians were

more likely to favour testing and treatment when considering

their recommendation to an individual patient than

when they were asked to consider how they would write

guidelines for a group of similar patients (Redelmeier

DA, Tversky A. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1162-4). The

framing of treatment data also has a powerful effect. A

new drug might reduce death rates for a given condition

from 4 per 100 patients treated to 3 per 100 -- a 25%

relative risk reduction. However, if the same data are

shown as a 1% absolute reduction, or represented fairly

by the statement that 100 patients must be treated with

the drug to save one life, then physicians become much

more cautious about recommending the new medicine

(Naylor CD, Chen E, Strauss B. Ann Intern Med.

1992;117(11):916-21).

As a final example of how politics and cognitive dissonance

can shape the use of evidence, Naylor pointed

out that in the early 1980s a rigorous randomized trial

undertaken by RAND researchers had shown that costs

were lower and outcomes similar with a comprehensive

capitated plan (then known as an HMO and now more

commonly termed an integrated delivery system) as compared

to Canadian-style health insurance (Manning WG

et al. N Engl J Med 1984;310:1505-15). The findings had

limited uptake in the US due to lobbying by organized

medicine and the private insurance industry, and were

downplayed here because of smugness about Canada’s

superior healthcare system and physician unease about

changes in compensation modalities. In part because of

our refusal to embrace such changes, the performance of

Canada’s healthcare system is now seen by many experts

as lagging behind a number of OECD peer nations.

Naylor closed the Kergin Lecture with two aphorisms

that encapsulated his theme of cognitive dissonance and

evidence-based medicine/policy-making. The first was

from a collection of essays on medical history published

in 1991: “The enduring lesson of history may be that

social change is inevitable and institutional progress possible,

but human nature is wonderfully intransigent” (1).

The second, arising from three decades of experience

as reflected in the lecture, was shorter: “How we think

is more important than what we know --- or think we

know”.

(1) Naylor CD, ed. Canadian Health Care and the State. Montreal:

McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1992, p12. |