Robert Stone Lecture

RETHINKING RESIDENCY TRAINING

Shaf Keshavjee, Bob Stone and Lee Swanstrom

Lee Swanstrom, Professor of Surgery at Oregon Health

Sciences University and Director of the Minimally

Invasive Surgery program, presented the Robert Stone

lecture “Rethinking Residency Training. Perspectives

gained from the Minimally Invasive Surgery Revolution”

at Toronto Western Hospital on Friday, May 13th 2011.

“The laparoscopic revolution began in the late 1980s

when Erich Muhe in Germany did the first laparoscopic

cholecystectomy. He performed 38 operations with one

death. He was reviled by his colleagues, lost his privileges,

was jailed and his wife left him, illustrating the dangers of

being the first. Eddie Joe Reddick brought the technique

of laparoscopic cholecystectomy back from France and

developed weekend courses for general surgeons in North

America. He charged $3,000 for each surgeon to come and

watch him perform the operation. He was able to retire

after five years, then bought a music publishing company.

Eventually, he lost all of his money and went back to work.

He was a better surgeon than he was a businessman.”

The standard approach to surgical residency training

is the Halsted apprenticeship model. Over a period

of 5 to 8 years, surgeons gradually take on increasing

responsibility. They are punished for their mistakes by

withholding progressive opportunities to operate as part

of this training paradigm. Under the old system, training

was long and the pace of surgical evolution was slow. For

example, it took 25 years of operating to achieve the first

survivor of esophagectomy.

Of all the radical revisions introduced by laparoscopic

surgery, weekend courses were the dominant new feature.

These introduced industry participation and marketing

as well as a short duration of training. Laparoscopic

cholecystectomy training had to be rapidly introduced,

so that all 20,000 general surgeons in the United States

could quickly learn the technique. This stimulated

innovation, the rapid development of new instruments,

and rapid introduction of new techniques into practice.

Surgeons who performed laparoscopic surgery could

control their own practice. Hospitals advertised the skills

of their laparoscopic surgeons to increase their market

share. By 2005, not only cholecystectomy, but nearly

every operation in the surgical armamentarium had been

done using minimally invasive surgical techniques.

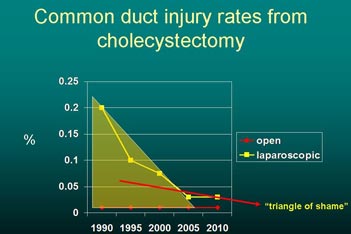

Fig. 1 The Triangle of shame

As it turned out, weekend courses were a mixed blessing,

because training for a weekend left the participants

with no muscle memory and no way for their teachers

to measure their competency. Common duct injuries

were common in the early learning phase of laparoscopic

cholecystectomy, occurring in 0.3% of cases - ten times

the rate of injury in open procedures. This period Lee

refers to as ‘the triangle of shame’. Laparoscopic surgery

proved to be bad for residency training, as teachers were

slow to pass their techniques on. It drove up costs and

introduced conflicts of interest with industry that verged

on the unethical.

|

It is now unacceptable to subject patients to such

learning curves. It stresses the surgeon, the operating

room staff, the healthcare system, and the patients.

With the publication of the IOM’s “To Err is Human”

mandatory improvement in learning new surgical techniques

was required. Current negative influences on the

development of laparoscopic surgery include its cost and

restrictions from the IRB. The reaction to this pushback

has been the development of centers of excellence, where

high volume is equated with expertise. The catch 22 of

this linkage is that it is difficult to get these high volumes

unless you practice in a center of excellence.

Bob Stone, Steve Gallinger and Hugh Scully

One possible solution to the problem is the NICE

Program (National Institute for Clinical Excellence)

introduced in the United Kingdom. The NHS, based

on a NICE evidence review, has decided not to pay for

open colectomy after 2014. In order to ensure that surgeons

become proficient at laparoscopic colectomy, the

government funds regional training centers and pays for

surgeons to attend courses. The government also hired

15 travelling expert surgeons to certify the competence

of those trained at the centres. They visit the surgeons in

the operating room, and proctor their performance. The

American College of Surgeons has also initiated a program

of regional training centers for surgery, but without

the mandate, funding or government backing of the

British system. We also have few measures of competency.

At this time, the American Board of Surgery requires

applicants to have FLS Certification (Fundamentals of

Laparoscopic Surgery) and there will soon be a similar

program for flexible endoscopy (FES). This is timely as

the American Gastroenterological Association and other

medical societies have taken a position that “surgeons are

poor practitioners of gastrointestinal endoscopy and we

shouldn’t be responsible for their training”. The burden

of adequate training and now guaranteeing to the public

that their surgeon is competent clearly rests on the

shoulders of the surgical community.

Short courses don’t work well for residents, and the

reduction in workweek hours has led to a situation where

“training is overreaching and underachieving in general

surgery”. The number of advanced laparoscopic surgical

cases seen in most residencies is usually low. For this reason,

minimally invasive surgery fellowships are needed,

plus the use of virtual reality and internet programs.

Will the system tolerate training as we knew it? How

will we accomplish the “10,000 hours of deliberate

practice?” demonstrated by Ericsson to be necessary for

expert performance. Lee proposes that we change our

thinking about residency training. “We should start at

the other end of the spectrum, introducing residents to

laparoscopic surgery at the beginning, rather than open

techniques. Over time, they can progress to performing

open operations in the 4th and 5th year.” Lee also proposes

that we proctor those who attend short courses,

design ways to measure their competence and train them

toward expertise. During the question period the appropriateness

of screening applicants for three dimensional

spatial sense was raised. Dimitri Anastakis pointed out

that studies completed here and published in the Lancet

show that it is not necessary to exclude applicants whose

three dimensional sense is less developed. They can eventually

be trained to perform at a competent level. Hugh

Scully asked if we are training enough general surgeons

to manage highway crash victims. Lee felt that the direction

that this is going is toward training trauma surgeons

and acute care surgeons, and the use of trauma centres.

Dimitri Anastakis asked how to pay for the $110,000

simulators needed for training. Lee answered that the

US Congress has been asked to address this as it should

be the responsibility of society. Shaf Keshavjee suggested

that industry should pay for the simulator in order to

prepare surgeons to use their $2.3 million devices later

on in their careers. Chris Feindel raised the question of

the effect of limited work hours. “We no longer train

the general surgeon as a universal genius capable of every

operation. The answer seems to be in specialization. ”

M.M with notes from Lee Swanstrom

|