Enhancing Surgical

Performance Using

Simulation

THE GEORGE ARMSTRONG PETERS PRIZE

The George Armstrong Peters Prize celebrates the memory

of Dr. Peters who was described by William Gallie

as "the best technical surgeon of all of my teachers".

The Peters prize is awarded to a young investigator who

has shown outstanding productivity during their initial

period as an independent investigator, as evidenced by

research publications in peer reviewed journals, grants

held, and students trained. In his Peters Prize Lecture,

Teodor Grantcharov, this year's winner, told us that "the

operating room is a high risk environment in which

patients encounter major complications in 3-17% of

cases. Between 44,000 and 98,000 patients in the

United States die because of medical errors. 40% of these

are operating room errors, of which 50% are avoidable."

"The current pressures on surgical education require a

revision in our thinking and training. The hours are shorter

for training, there are decreased clinical opportunities for

residents compared to their teachers, the technology has

become more complex, there is a focus on error, patients

are demanding, and there is a focus on quality of life for

residents. All of these pressures diminish the opportunities

for trainees. Currently, we still hold to the idea that time

is the constant and proficiency is the variable. We still use

subjective assessment, learning by doing, and there has been

little change in the curricula over the last several decades. It

is time for us to move from a fixed time to proficiency as the

criterion for completion

of training."

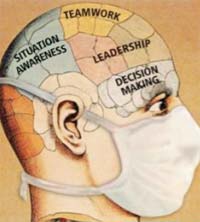

Figure 1

|

Teodor's first

research project

in Toronto asked

the question: Can

simulation training

produce skills

that transfer to the

operating room?

The study results

clearly confirmed

the effectiveness of

simulation training in shortening the learning curves

for surgical trainees. The simulation-trained residents

achieved proficiency before they entered the operating

room. When the cost of training techniques is estimated,

operating room training is far more expensive and the

transfer effectiveness of simulation training is more than

twice that of box or actual operating room experience. A

competency based curriculum accounts for differences

in ability and skill at the outset, eliminates the learning

curve in the operating room, and pre-trained residents

learn much more effectively when they do enter the

operating room. It also ensures that basic competencies

are achieved and tested. The essential components of

a successful curriculum based on American College of

Surgeons consensus meetings (1) include development of

cognitive, psychomotor and team skills. The animal lab

serves as the final testing ground before the operating

room. Team training has been largely ignored in surgical

education and there is a need for educational interventions

in this domain (currently only half of the Canadian

and 30% of the US programs offer team training component).

Figure 1 illustrates the essential elements of

team training: situation awareness, leadership, teamwork

and decision making.

|

Teodor told us that error is inevitable if humans are

involved and the "deny, forget, ignore and repeat" response

is unacceptable. The solution is performance analysis, education,

and deliberate practice to mitigate errors and interrupt

the chain of events that leads to adverse outcomes (Fig.

2). Teodor's group has developed a black box multichannel

performance analyzer to reduce surgical errors. It records

many variables in the operating room, including noise and

distractions. The pathway for interrupting this is analysis,

identification, awareness, early detection.

Vanessa Palter, working with Teodor, reported a

randomized control trial in the Annals of Surgery, comparing

conventionally trained with competency-based

curriculum trained surgical residents. The difference was

striking (Fig. 3).

In the discussion period, Jim Rutka asked about the

problem of taking uncorrectably non-proficient surgeons

all the way through training. Teodor answered that 5%

of residents show outstanding abilities at the outset, 8%

never become proficient and the rest achieve proficiency

with training. Training individuals who don't have the

innate abilities is a waste of personal and training-system

resources. To find a way to screen out those who should

not become surgeons, Teodor is working with medical

student volunteers, using functional MRI to determine

aptitude or ineptitude.

M.M.

(1) Zevin B, Levy JS, Satava RM, Grantcharov TP. A Consensus-Based Framework for Design, Validation, and Implementation of Simulation-Based Training Curricula in Surgery. Journal of the American College of Surgeons: October 2012: 215 (4): pp 580-586.e3

|